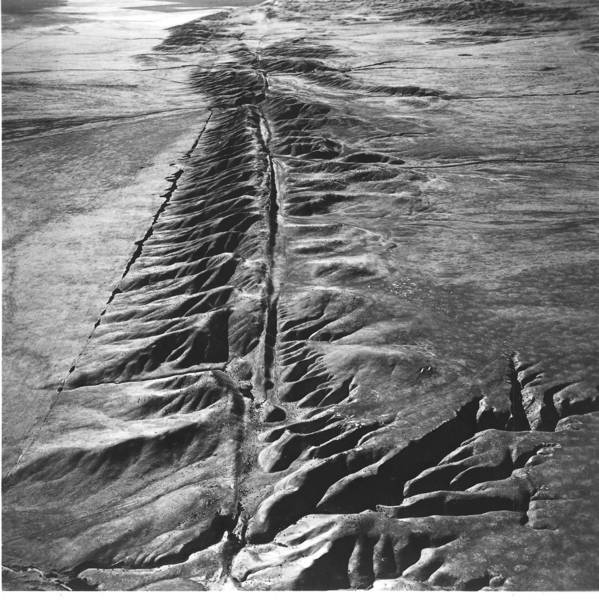

For decades, scientists have assumed the central portion of California's San Andreas fault acts as a barrier that prevents a big quake in the southern part of the state from spreading to the north, and vice versa. As a result, a mega-quake that could be felt from San Diego to San Francisco was widely considered impossible.

For decades, scientists have assumed the central portion of California's San Andreas fault acts as a barrier that prevents a big quake in the southern part of the state from spreading to the north, and vice versa. As a result, a mega-quake that could be felt from San Diego to San Francisco was widely considered impossible.

But that key fault segment might not serve as a barrier in all cases, researchers wrote Wednesday in the online edition of the journal Nature.

Using a combination of laboratory measurements and computer simulations, the two scientists showed how so-called creeping segments in a fault — long thought to be benign because they slip slowly and steadily along as tectonic plates shift — might behave like locked segments, which build up stress over time and then rupture.

Such a snap caused the 9.0-magnitude Tohoku-Oki earthquake that hit Japan in 2011, triggering a tsunami, killing nearly 16,000 people and destroying the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Forecasters had not believed such a large quake was possible there.

She navigated segregation to become an esteemed mathematician — and today, her work helps billions of...

She navigated segregation to become an esteemed mathematician — and today, her work helps billions of... NASA is cutting short a mission at the International Space Station due to a medical issue...

NASA is cutting short a mission at the International Space Station due to a medical issue... Scientists may have discovered an explanation for a cosmic mystery uncovered by the James Webb Space...

Scientists may have discovered an explanation for a cosmic mystery uncovered by the James Webb Space... Three more Chinese astronauts, or taikonauts, are now marooned in space following the successful return of...

Three more Chinese astronauts, or taikonauts, are now marooned in space following the successful return of...